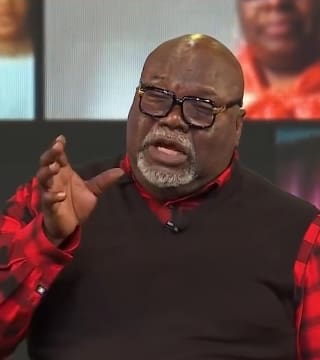

TD Jakes - Finding Power in Your Memories (05/12/2025)

Using the Passover in Exodus and the Lord's Supper as examples of God creating defining memories for His people, the preacher turns to Psalm 137 where the exiles in Babylon weep bitterly when they remember the lost glory of Jerusalem after its brutal destruction. He connects their profound grief over irreversible loss and displacement to the unprecedented trauma of the current era—marked by pandemic shutdowns, isolation, and death—emphasizing that the pain of remembering what was "normal" often hurts more than the emptiness itself.

God Creates Defining Moments and Memories

God understands the importance of moments. God understands the power of memories, and there are some things God does so that you will define your relationship with Him based on a memory. He told Moses, “I’m going to bring the children of Israel out of Egypt. I’m going to cause the death angel to pass over by night. I want you to put blood on the doorpost and on the lintel.” He said, “When the death angel passes over and sees the blood, he will pass over you.”

That one moment became a point of reference for the next thousand years. God referred to this: “Am I not the God who brought you out of the wilderness? Am I not the God who brought you out of Egypt? Am I not the God who delivered you from the hand of Pharaoh?” That one moment was done so they would have a memory, so that whatever they faced—the Hittites, the Jebusites, the Philistines—whatever they encountered, they would remember that moment and use it as a point of reference to build and strengthen their faith, to define their relationship with God and say, “If God can do that, He can do this too.”

In the New Testament, on the night before Jesus was to be offered up, He had a Passover dinner with the disciples, and He brought them together. He took the bread, broke it, blessed it, gave it to them, and told them to eat. He said, “This do, what? Say it again, say it again: 'This do in remembrance of me.'” So, as often as you do this, you show forth the Lord’s death till He comes. He is replacing the blood of the lamb with the blood of Jesus. He says, “I’m going to give you a new memory, a new reflection, a new way of identifying yourself.”

As often as you do this, you let me know, “I still remember, I still remember. I hate it when people forget. I hate it when they forget. I’m not talking about forgetting where you put your watch or where you parked your car; I’m talking about forgetting that I’ve been good to you, forgetting when I helped you out of trouble. I don’t mind being betrayed, but I hate being betrayed by people I was good to. It just gets on my nerves to say, 'How did you forget? Am I not the same person that you called at two o’clock in the morning when you were in trouble, and you talked to me at 2:10?'” People forget; they forget, they forget, and they walk away from you, failing to remember the things that matter most in life.

The Raw Pain in Psalm 137

In our text tonight, this is probably the bloodiest Psalm of all 150 divisions of the Psalms. It is bloody because the author openly and adamantly hopes God kills their enemies and prays that He kills their children and everyone associated with them. It is raw and honest; as young people say, “Keep it 100.” He doesn’t try to impress us with being deeply spiritual. His emotions are all over the place. In the course of nine verses, he is spiritual one moment, remorseful the next, and angry the next moment—all incorporated in nine verses of the 137th division of Psalms.

In order to appreciate the magnitude of what is happening here, you must understand that he has left Jerusalem on the run. His home has been besieged by the Babylonians, the nine tribes have been lost, and only a few have stayed in Jerusalem. They have been fiercely beaten—not just beaten like you’ve got a weapon, but beaten like you’re a dog, like you’re an animal. They had been beaten until they were bloody, battered, tattered, and torn. The women had their clothes yanked off of them and were raped, denied any dignity or ability to resist.

The Brutal Destruction of Jerusalem

The men who resisted were castrated, with blood running down their legs and chains wrapped around their ankles. In the hot Palestinian heat, they were driven away, defeated out of their own country, their own land, and their own customs, away from Jerusalem. Oh, Jerusalem! Away from the place where they woke up in the morning to the smell of baking bread and could hear the cobbler as he began to get out his hammers to prepare to make shoes, the coppersmiths and the sound of them early in the morning, and the women singing down by the river as they washed their clothes, singing Hebrew songs and dancing on the riverbanks.

There was no place like Jerusalem, but now it lay in ruins. There is no hammering, no nailing, no bread being baked. Instead, the smell of fresh-baked bread has been replaced with the stench of burning flesh, the screams and anxieties of Hebrew boys and girls who are killed like you would kill a roach. The men have been castrated, and the women have been humiliated as they are dragged away from Jerusalem, the holy city that not only defines their culture but also defines their faith—everything about who they are.

Who would have ever thought that Jerusalem could be lost? It was lost to them; only a few remained, while the rest were dragged away. It was a bitter moment, a painfully crushing moment, because when they were dragged away, they never knew for sure whether they would ever get back to Jerusalem again. There are some things when you lose them you can’t be sure you’ll ever get them back. That’s why you have to take care of things when you have them because you have no guarantee that if you lose them, you will never get them back again. I can see the young, handsome Hebrew boys with hair flowing down their backs, blood running down their legs, and sweat trickling down their brows, looking back at Jerusalem on fire, trying to etch it in their minds so they would never forget Jerusalem.

Jerusalem—the place of Solomon’s temple, the beautiful, majestic Solomon’s temple—you remember the one where, when the temple was finished and built, the Shekinah glory sat down upon it, and the priests laid prostrate on the floor? It was so amazing that Solomon had asked, “What would happen if you change your mind and shut up the heavens so there’d be no more rain?” God said, “If my people, who are called by my name, shall humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then will I hear from heaven and forgive their sins and heal their land.” They weren’t supposed to lose Jerusalem. The worst that should have happened was that they messed up and had to repent. They have lost Jerusalem, lost what defines them, what gives them distinction, what sets them apart.

Losing What Makes You Unique

Do you not know the enemy wants you to lose what makes you distinctive—your integrity, your honor, your class, your personality, your disposition, the uniqueness of you? There is never going to be another you. Two hundred years from now, nobody will have your fingerprint; nobody will have your voice pattern. You are one of a kind—there has never been one before you, and there will never be one after you—yet the enemy wants to destroy what makes you unique or make you so envious of other people that you give up on being you and trade a designer’s original for a cheap copy of something you saw.

You must realize there will never be another you. They realized there would never be another Jerusalem, and they defined themselves by Jerusalem, and it was gone. Despite the pain, I don’t think I would like to take a walk if I were castrated—it just doesn’t sound appealing. I’ve never been castrated, but it doesn’t sound like something a guy would want to do with blood running down his legs, and yet they walked 540 miles on foot, bleeding, hurting, and suffering to nothing—no music, just the sound of the rattling chains around their ankles. Those who were known for their liberty had become captives, bound.

Weeping by the Rivers of Babylon

When we step into our text, we find ourselves next to people who have carried their bloody, beaten bodies away from the holy city of Jerusalem and found themselves in a strange place called Babylon. Brothers and sisters, ladies and gentlemen, we find ourselves in a strange place today; we find ourselves in a place we have never been in before. I have seen many things happen in my life.

I remember the “I Have a Dream” speech when Dr. King spoke; I remember the day they shot him in the motel in Memphis. I was a young boy, but I still remember. I remember his funeral and the horse-drawn carriage that carried his body. I still remember Mahalia Jackson singing “Move On Up a Little Higher” at the funeral. I remember it like it was yesterday. I remember the Vietnam War, the hippies, and a lot of things—like when John Kennedy was killed right down here in Dallas, and I remember when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. I remember when we were lied to about Vietnam, and I remember Watergate and the scandal with Nixon. I remember the civil rights movement, the Pettus Bridge, and when they carried the charred bodies of little Black girls out of a church service.

I remember Emmett Till and Medgar Evers; I remember all of that. I’ve witnessed all of that in the span of my life, but I have never seen a time like this. I have never seen a time when churches were shut down, and those who dared to come were masked as if they were preparing to rob a bank. I’ve never seen a time when you had to pray about whether it was safe to go to the grocery store. I’ve never seen a time when people were taking your temperature before you walked into a mall, and I’ve never seen a time when hundreds and thousands of people have died from an invisible disease—you can’t tell whether you’re walking into it or not. I have never seen a time like this.

So when my brother sits by the rivers of Babylon, I sit there with him. I sit there with him because he has never seen Babylon, and I have never seen this. The Bible says he sat down by the rivers of Babylon and wept. When I studied the rivers of Babylon, it is in all likelihood not so much a river but a canal built from the rivers because the Babylonians irrigated their crops by building canals that caused water to flow so they wouldn’t have to carry water so far to water them. This man-made river is filled with man-caused tears, and as the tears run down his face, the rivers flow until you cannot tell one from the other. We sat by the rivers of Babylon, and we wept—not because of the pain in our bodies or the lacerations in our flesh, or the discomfort of the chains around our ankles; we wept when we remembered what we lost.

Oh, what we lost! I come in here every Sunday and preach, and it really doesn’t bother me to preach in an empty building. It didn’t bother me; it didn’t upset me because it put me in a war mode. When I get into war mode, fighting becomes the optimum drug, and all I’m going to do is fight. I’ll fight whether anybody’s sitting there or not to let the devil know, “You ain’t going to take me out like this! I’ll fight you.”

I’ll preach in a room by myself. It didn’t bother me to see an empty room, but the other night—on New Year’s Eve—when they showed a room full, the balcony loaded, the congregation jumping, and the music everywhere while the traffic was backed up, I looked at it, and tears welled up in my eyes because I remembered—I remembered what normal looks like. I remember what we lost; I remember that. I remember the thunderous sound I’m used to hearing on Sunday mornings when thousands break out in spontaneous praise, and the aisle is filled with dancing. It’s funny; the emptiness didn’t hurt like the memory of the fullness. It was all I could do to fight back the tears when I remembered what was.